Oysters, Bacteria, and Bay Waters: What a New Delaware Study Reveals

Oysters are Delaware’s pride: local delicacies on the half shell, natural water filters, and critical players in coastal ecosystems. But they’re also tiny sponges for everything in the water around them—including bacteria. A new study out of Delaware State University puts that under the microscope.

The Study at a Glance

Researchers investigated seawater and oysters from Sally Cove in Rehoboth Bay, monitoring samples from July to October 2023. Using molecular tools (PCR and qPCR), they screened for eight types of bacteria known to affect human health. Both off-bottom cultured oysters (grown in floating cages) and bottom-cultured oysters (grown directly on the bay floor) were tested, alongside seawater from the farm and a control site with no oysters.

What They Found

The results are sobering:

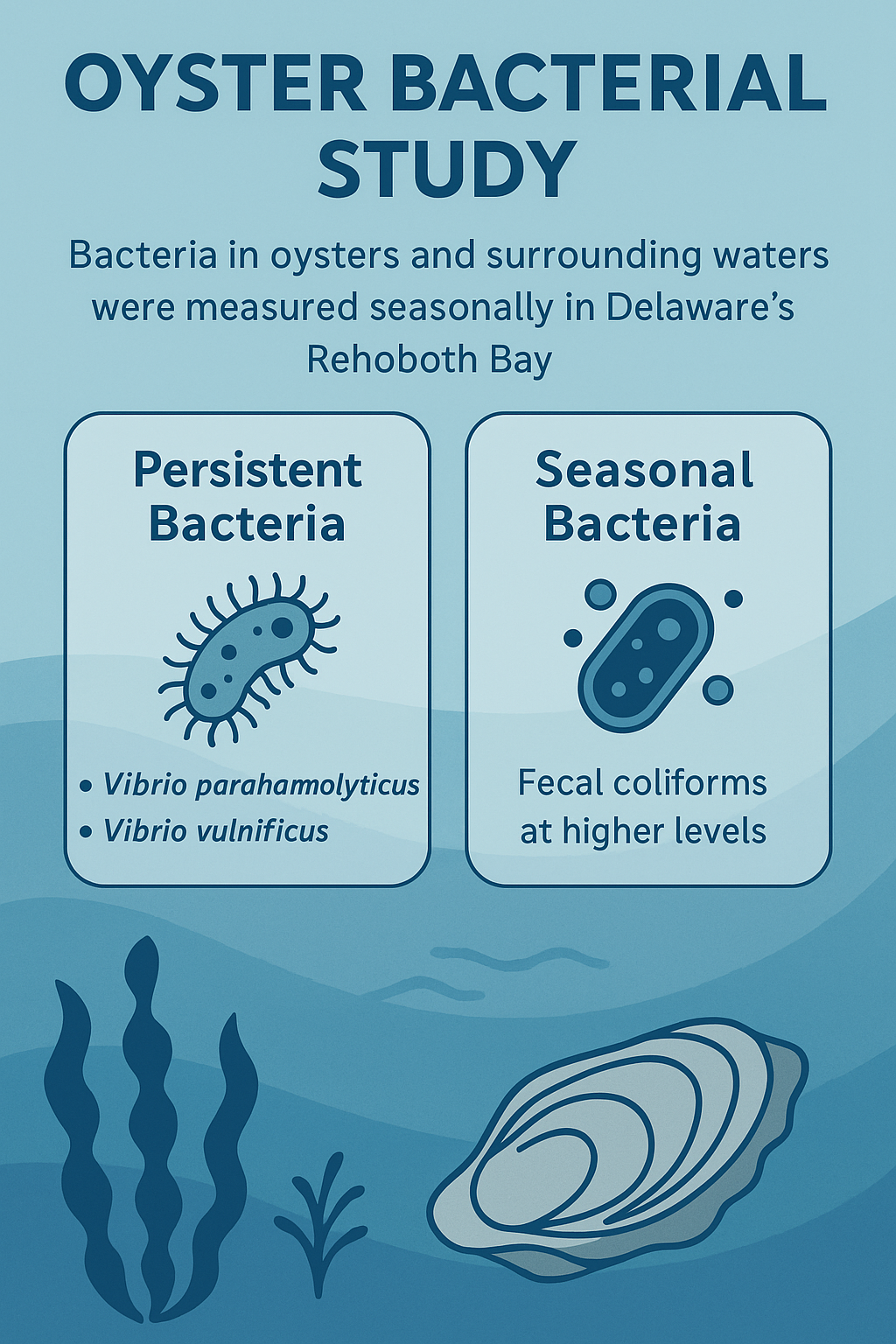

Persistent Bacteria – Several pathogens stuck around all season, including Vibrio parahaemolyticus, E. coli(STEC), Salmonella enterica, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Clostridium species

Seasonal Shifts – Shigella and Listeria monocytogenes were present in summer (July–September), but disappeared by October. Interestingly, Shigella lingered longer in bottom-cultured oysters than off-bottom

Environmental Conditions – The bay water ranged between 15–29°C, salinity around 29–32 ppt, pH 7.2–7.9, and dissolved oxygen 3.8–8.1 mg/L—conditions that are unfortunately very favorable for bacterial

Why It Matters

Oysters are filter feeders, drawing in 5–25 liters of water per hour. That’s great for water clarity, but it also means they can concentrate bacteria from human waste, storm runoff, or agricultural inputs. Eating raw oysters from contaminated waters increases the risk of foodborne illness—something the U.S. sees far too often, with seafood accounting for thousands of outbreaks each year.

A Takeaway Quote

The authors drive home the public health implications:

“Consuming raw oysters from Sally Cove poses contamination risks from several bacteria, especially in the summer months.”

The Bigger Picture

This study doesn’t just highlight a local issue—it underscores a global one: how aquaculture, water quality, and human activity intersect in our food supply. For Delaware, it’s a call to improve seafood monitoring, develop rapid onsite detection tools, and continue studying how seasonal changes affect contamination risks.

At Delaware Analytical, we are closely following these advances in seafood safety and water testing. With our laboratory expertise, we aim to support environmental monitoring projects that help protect consumers, producers, and ecosystems alike.